Tonight is Bonfire Night, Firework Night, nowadays usurped by Hallowe’en as the most popular celebration of autumn-to-winter transition, but still a folk festival of note. Many people are aware that the fires and fireworks commemorate the failed gunpowder plot of 1605, but few know more than the name of the terrorist whose effigy we burn on Guy Fawkes night.

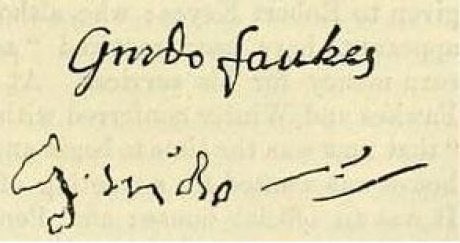

The catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes, who came from from Yorkshire, spoke French when captured and signed himself ‘Guido’, using the Italian or Spanish form of the name (his autograph, before and after torture had been applied, is below). He may have begun the practice when fighting in the Spanish army in the Low Countries, although Italian names were considered fashionable and were sometimes adopted by English gallants. Guy is the French form of old Germanic Wido, either meaning ‘dweller at the forest margin’ or a nickname from ‘wide’ as bodily description or location (an open, flat region).

The English surname Fawkes, also archaically spelled Fauks, Faukes and Fakes, derives from the German name or nickname Falco which probably originally referred to a person thought to resemble a falcon. Falco became Faulques in Norman French and was adopted after the Conquest, the first attestation coming from 1221.

While in London preparing to blow up parliament, Fawkes posed as a servant in the entourage of Thomas Percy, a fellow conspirator who had access to the parliamentary precincts. Fawkes’ less than imaginative choice of alias was ‘John Johnson.’

Guy’s wide-brimmed headgear, crudely imitated on effigies and now caricatured as a ‘V for Vendetta’ hat, is correctly termed a ‘sugarloaf hat’, since its high, flat-topped crown resembled the sugarloafs imported from the colonies in the Stuart period.

Isla Guy Fawkes, or Guy Fawkes Island is actually two small uninhabited islands and two smaller rocks lying in the Pacific Ocean off the Galápagos Islands which are owned by Ecuador. The name might have been given after a fiery volcanic event had been witnessed, but was more probably bestowed by buccaneers who viewed Guy as a hero and one of their own.

Fireworks did not just take off (pun intended) in England after the Gunpowder Plot. They first became popular in the reign of Henry VII. Queen Elizabeth I loved them and appointed a ‘Firemaster of England’ to arrange displays.

Bonfire (first recorded in 1483) is not, as Dr Johnson and others have claimed, French ‘bon feu’, (French would be ‘feu de joie’, ‘grand feu’) but ‘bone-fire’, a collection of burning bones or an open fireplace or outdoor pyre into which bones were thrown, after feasting for instance. By 1581 the word was also being used to refer to a fire in which heretics were burnt. Celebratory fires were ordered to be lit each year to commemorate the failed conspiracy against the Crown, but Guy’s effigy was only placed upon them from the1700s.

Guy himself was not executed by burning, a fate reserved for those found guilty of heresy. He and the other condemned plotters were indeed Catholic dissidents, but the state wanted to avoid civil disturbances so accused them of treason, for which the punishment was hanging, drawing and quartering, carried out at length and in front of spectators. Fawkes managed to cheat the hangman by falling or throwing himself from the ladder leading to the scaffold, breaking his neck.

Guy Fawkes’s first name lived on, coming to mean by 1806 his effigy, then a grotesquely or poorly dressed person or eccentric. By extension a verb form arose (first attested in 1872) meaning to hold (someone) to ridicule. At the end of the 19th century in American colloquial usage the word had come to mean simply ‘a fellow’, from which we get our modern all-purpose, sometimes gender-neutral ‘guy’.