In the last two days we have been treated to several (sadly superficial and unoriginal) press articles* revealing the efforts of posh persons to disguise their accents. The assuming of so-called mockney or Estuary English, and the seeming decline of so-called R.P is nothing new, and I wrote about it back in 2013…

TEN WAYS WE DISPARAGE THE ACCENTS OF OTHERS…

* A nasal twang

* A thick brogue

* A supercilious drawl

* An incoherent babble

* A boring non-accent

* A provincial burr

* A Home Counties whine

* …what comes out is a kind of screeching

* Your phoney telephone voice!

* ‘…this fake ghetto-speak that seems to have swept across the country where rather than saying ‘like’ it’s ‘lac’, and ‘nine’ is pronounced ‘naan’. D’y’a know what I mean? Drives me so crazy I can’t listen to Radio 1 any more.’

The Greater London twang from a public school boy, the refined little ‘haitch’ from a Hyacinth Bouquet, the mysterious vowels of someone pretending not to be from Birmingham: these are all friendly little signs saying: I’m no threat to you, honestly; given half a chance I’d erase my entire self and start again.’

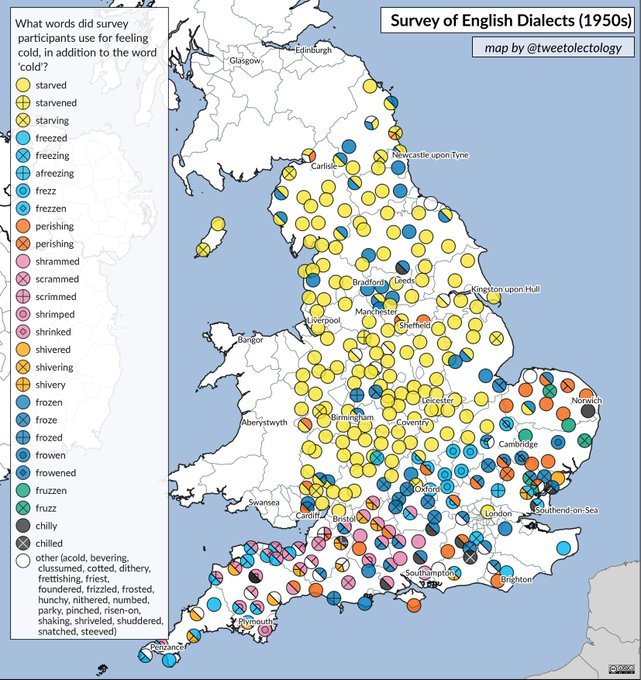

In 1966 Michael Aspel was carpeted by the BBC for selling records of elocution lessons featuring his voice and that of Jean Metcalfe, the ads for which implied, the corporation said, that broadcasting required a posh voice. For virtually the whole of the 20th century, and some would say still today, the English (and not the Scottish, Welsh and Irish) have been defined above all other markers (dress doesn’t count any more, the school they attended may remain a secret) by their accents. And not by simple regional variance as in other European cultures, but by nuances associated with social class. It was Alan Ross of Birmingham University who in 1954 coined the terms ‘U’ and ‘non-U’ (later popularised by the writer Nancy Mitford) to differentiate the behaviour of the upper classes and the masses. Ross believed, though, that by the mid–fifties the upper class was truly distinguished ‘solely by its language’; its vocabulary and especially its intonation. It occurred to me that by this measure, looking at the rough statistics for public school and Oxbridge attendance, in the 1950s and 1960s, at least 94% of the population were speaking with the ‘wrong’ accents. Alone at the top of the linguistic hierarchy was what linguists rather unhelpfully termed ‘RP’ for ‘received pronunciation’, the non-regional high-status accent acquired from family or from one’s place of education and actively promoted by the BBC in particular. Some way below in terms of perceived respectability were the more neutral forms of south-eastern English and Morningside Scots (the lilting educated Edinburgh accent). Clustered at the bottom of the imaginary pyramid were all the regional accents of the UK, with surveys showing that some – Norfolk, Birmingham, Glasgow, Tyneside, for example – were perceived more negatively than others by the general population.

The late Malcolm Bradbury, novelist and critic, writing back in September 1994, asked rhetorically, ‘Is there today a standard English? Estuary English, sometimes called Milton Keynes English, seems to be bidding for the position.’ He was referring of course only to the English of England, not the multiple dialects and accents of the wider anglosphere. He went on to characterise this apparent novelty: ‘It seems to have been learnt in the back of London taxis, or from alternative comedians…it’s southern, urban, glottal, easygoing, offhand, vernacular…apparently classless, or at any rate a language for talking easily across classes.’ Interviewed in 2001 Shirley Jones, a 22 year-old student from Stockport affirmed, ‘Estuary English is nice to the ear…it’s 50/50 cockney and young southern professional… I prefer it to the northern accent but I resent it because of the stigma of not speaking it.’ The idea of a replacement ‘standard’ accent actually emerged in 1984 and was promoted by David Rosewarne of the University of Surrey (who chose the term since the accent he had identified straddled the Thames), later by Paul Kerswill and by the Linguistics and Phonetics department at UCL under the panjandrum of phonology Professor John Wells.

Estuary is only the most recent attempt to describe an accent, or rather a spectrum of similar accents, that have been heard across the Greater London area and in Essex, Kent, Middlesex, Surrey and Sussex for a century or so. It has been linked to the exodus of true Cockneys from the East End since World War II, but my own grandmother, a teacher who lived in Woolwich in Southeast London, could distinguish precisely the regional nuances in a pre-war London-wide ‘lower-class’ accent. Something like what is now called Estuary was characterised by my father back in the early 1970s variously as the ‘home counties whine’, the ‘southern drawl’ and the ‘polytechnic accent’; sometimes simply as ‘adenoidal English’, as exemplified by David Frost when presenting TV satire programmes in the early 1960s. Before that ‘breakthrough’, broadcasting had permitted only RP (or the RADA English of trained actors) or the so-called mid-Atlantic accent of game-show hosts like Hughie Green. Certainly the broadcast media reversed its prejudices during the 1980s and 90s, actively welcoming regional and ‘ethnic’ accents as well as the deliberately classless ‘DJ-speak’ which had been evolving on commercial radio since its beginnings. It is now getting frustratingly hard even to find illustrative examples of RP on the airwaves.

Strictly speaking Estuary shouldn’t be confused with ‘mockney’ (mock-cockney) although it often is. The latter is the exaggerated or feigned working class London accent, typically employing glottal stops and ‘f’ in place of ‘th’, as used by violinist Nigel Kennedy, celebrity chef Jamie Oliver and, in earlier times and with a camp inflection, by 60s icons Mick Jagger and David Bailey. ‘Mummerset’, the attempt, often by naturally posh-talking actors, at a non-specific West Country burr (made famous by the radio soap The Archers and parodied on the comedy radio shows Beyond our Ken and Round the Horne by the characters Arthur Fallowfield and Rambling Sid Rumpo), is very rarely encountered these days. It may also be significant that regional accents like Brummie, Geordie and Scouse haven’t been re-labelled in recent years. This isn’t to say that they haven’t evolved or been modified by contact with other styles of speaking. Linguists have demonstrated what they call ‘levelling’ of dialects and accents, whereby regional forms lose their most pronounced (sorry) features and incorporate elements from other sources. One phenomenon I have noticed, but which has not been commented upon in any depth is a tendency by younger speakers in most parts of the country towards an imitation of childish or ‘lazy’ pronunciations of individual sounds – again, ‘f’ or ‘v’ for ‘th’, ‘w’ for ‘r’ and glottal stops wherever possible, and of more rhythmic, drawled intonations probably unconsciously influenced by Australian and American speech patterns…

…Prestige comes from the places in which a particular form of speech is practised: the court, the universities, the capital city, the broadcasting authority. (BBC insiders used to tell each other that their ‘BBC English’ was superior because clear and simple, not because they were trusted opinion-formers: we may think otherwise). In a local setting the prestige pronunciation of family names is the one, however unexpected, favoured by the family itself; of place names it used to be that of the surveyor or the squire but now is that of a majority of local people. In the urban playground it isn’t the teacher’s English that is prestigious, but cool ‘yoof-speak’ – that multiethnic vernacular again.

So when horny-handed Uncle Gerald disses his niece’s ‘fancy’ pronunciation, or a Head Teacher despairs at her pupils’ ‘impenetrable dialect’, their criticisms could be idiosyncratic – a simple personal preference – or could stem from social prejudice, either regional or class-based. What they can’t possibly be is a reasoned, objective assessment of a cluster of English phonemes. It’s actually more complicated: Uncle Gerald doesn’t seem to have picked up on the fact that ‘posh-ish’, a modest, moderate form of the old RP seems to have made something of a comeback, thanks perhaps to the makeup of David Cameron’s government. At the same time, if that Head Teacher wants to get on the radio, or just hopes to do some paid podcasting for educational purposes, she would be well advised to play up any regional or ethnic inflections in her voice, any cues that will key into the diversity of the audience at large. (I’m still smarting myself at being turned down for the job of presenting a radio series on changing language on the grounds, according to the producer, that my voice ‘wasn’t working class or ethnic enough.’). These are the currents and cross-currents in the national conversation that reflect – or dictate – our reactions to the sounds we hear…

…If there is no scientific reason why one set of sounds is superior to another, why do both individual sounds and wider accents change over time, and why do those hurtful, discriminatory assumptions about them keep on coming? When the author Robert Graves returned to Oxford in October 1961 to take up the Professorship of Poetry, The Times reported him as saying, ‘Only the ordinary accent of the undergraduate has changed. In my day you very seldom heard anything but Oxford English; now there is a lot of North Country and so on. In 1920 it was prophesied that the Oxford accent would overcome all others. But the regional speech proved stronger. A good thing.’

“I speak Black Country. I speak History.”

– Dave, from Halesowen

In a 2012 survey British listeners said they found the dialect of the city of Birmingham, England to be ‘boring’, ‘wrong’, ‘irritating’, ‘grating’, ‘nasal’, and ‘whingey’; very interestingly, non-native listeners found it ‘nice’, ‘melodic’, ‘lilting’ and ‘musical’. Prejudice pops up even when the sounds in question sound exactly the same to outsiders. Black Countryman Steve, recorded for the BBC ‘Voices’ survey, opined:

‘The Birmingkham accent I don’t like. In the Midlands you’ve go’ the Black Coontray an’ Birmingkham an’ there’s a massive divoide there, bikos people in Birmingkham theyr’e called ‘Brummies’ or ‘0121-ers’ [from the phone prefix] an’ they ten’ not to mix too mooch wi’ the Black Coontray people, boot the Black Coontray – what you’ll foind is they’re the salt of the earth, they’re really noice people.’

The Black Country way of speaking is a marvellous example of the fact that regional English dialects – and American English, too, for that matter – have as much if not more claim to be the authentic voices of an English heritage, and not the Standard English of the southern educated classes, an essentially artificial variety with only a short history. The dialect of the Black Country area remains perhaps one of the last examples of early English still spoken today. The word endings with ‘en’ are still noticeable in conversation as in ‘gooen’ (going), ‘callen’ (calling) and the vowel ‘a’ is pronounced as ‘o’ as in sond (sand), ‘hond’ (hand) and ‘mon’ (man). Other pronunciations are ‘winder’ for window, ‘fer’ for far, and ‘loff’ for laugh – exactly as Chaucer’s English was spoken. Other features still detectable today resemble closely Shakespeare’s iconic version of our language in its Early Modern or Elizabethan incarnation.

THE TEN BEST-LIKED BRITISH ACCENTS

According to a 2013 survey by Roxy Palace online casino

1. Irish – 28 per cent

2. West Country – 19 per cent

3. Geordie – 17 per cent

4. Mancunian – 11 per cent

5. Glaswegian – 8 per cent

6. Scouse – 6 per cent

7. Yorkshire – 5 per cent

8. Welsh – 3 per cent

9. Brummie – 2 per cent

10. Essex – 1 per cent

(Do you think the order here would have been the same thirty years ago, and can you see what’s missing?*)

* It’s RP, or Standard English!

To many people’s surprise long-lost recordings unearthed in 2010 revealed that Queen Victoria had an unmistakeably German accent. A century later Lady Diana and Prince Charles were always going to be incompatible, some said, since they spoke in different ways: his accent a clenched military/nursery style from long ago; hers, a plaintive attempt at classlessness. Surely, though, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II’s English is an icon of steadfastness, a model to aspire to? For most people nothing is more respectable than ‘the Queen’s English’. But according to Dame Helen Mirren even Her Majesty has, unconsciously or perhaps deliberately, let her accent slide. Speaking in 2012 the actress, who was reprising her Oscar winning role as the monarch, said that Her Majesty’s words have become more ‘estuary’ as she has got older. ‘Her voice has changed, and I can use that – she had a terribly posh voice when she was young,’ Dame Helen said. ‘But now even the Queen, while she isn’t quite dropping the ends of her lines – though her grandsons do! There’s a tiny bit of estuary creeping in there’.

This was not the first time that the Queen has been accused of dropping her vocal standards. A millennial study of the Queen’s Christmas Day broadcasts showed that her accent had gone from ‘clipped’ in the 1940s to one more in common with a BBC Radio 4 announcer by 2000. In 2006 another study claimed that she had gone from ‘cut glass URP’ (Upper Received Pronunciation) towards the more democratic Standard Received Pronunciation and its close relative, Standard Southern British English. Now listen to a 14-year-old Princess Elizabeth make her first radio address to the children of the Commonwealth on October 13 1940. Then Listen to the Queen’s ‘thank you’ message to the nation after the Diamond Jubilee celebrations in June marking her 60 years on the throne.

Ten per cent of the population would apparently hesitate to employ her son Charles, because his voice is too ‘posh’, if a survey published in 2012 is to be believed. The Prince of Wales is unlikely to be losing sleep over this revelation, but his is an affliction that the rest of the family has quietly been working on. In the survey about employable voices, people disliked accents that were too ‘plummy’, but the Royal Family’s has never been plummy. Nor does it resemble the once dominant ‘lah-di-dah’ tones of the County Set or the snooty Oxbridge drawl. If the Queen has moderated her accent, it remains distinctly that of a remote elite. Her grandchildren William and Harry, in contrast, have moved towards the standard speech of their friends from school and Army. They sometimes come close to a new way of speaking adopted by the privileged younger generation known as ‘yatties’ or ‘ok-yahs’ which mixes glottal stops with a rising inflection (interspersed with gushing squeals, mainly though not exclusively by the females).

As Daily Telegraph pundit Christopher Howse noted, the current Cabinet is, of course, equally expensively educated and equally petrified of being taken for toffs. ‘The Conservatives have bought up a job lot of glottal stops that New Labour had stockpiled for deployment within 45 minutes of being summoned to the television studio. It is just as silly for David Cameron and George Osborne to prune their consonants’, he observes, ‘like mangled old yews around their country houses, as it was for Edinburgh-born Tony Blair, educated at Fettes, the Eton of North Britain to affect a classless mateyness.’

It may not actually be class prejudice that explains the reluctance by a quarter of the 300 ‘bosses’ polled in 2012 to give a job to football legend David Beckham. In the case of Beckham’s voice it’s more probably his unique nasal tones rather than his Chingford accent that are rather off-putting. Nor is it her Dagenham origins that undermine the employment prospects of reality TV star Stacey Solomon, whom 46 per cent of bosses could not picture as an executive. In her case, it’s what she says, not the way she says it. ‘I’m like, ‘Oh fanks, Mum!’’ she suddenly exclaims, the next minute yelling: ‘I don’t even like coffee. I fink it stinks!’ The Vicky Pollard delivery can be done in any number of different voices, but none would inspire business confidence.

And anyway, do the speech patterns of successful businessmen impress the rest of us? The bosses in the survey approved, for example, of the accent of Peter Jones from the TV series Dragon’s Den. But Jones and his ilk haven’t really got accents. That’s the point. When he gives his Golden Rules for Success the Dragon sounds, not like the meritocratic version of classless that my father could produce, but neutered, like a recorded safety message on an airliner: ‘Place the lifejacket over your head and secure the tapes at each side.’

Following the Queen’s death in September 2022 the BBC published a detailed commentary on her accent and the changes it underwent:

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20220915-what-the-queens-english-told-us-about-a-changing-world

* Those articles are here: