In January and February 2016 Bethlem Museum of the Mind is staging an exhibition devoted to the art of Louis Wain, once a patient at the Bethlem Royal Hospital, formerly the notorious ‘Bedlam’ asylum in Southeast London where in earlier times the public came to gaze at inmates. Wain is categorised as a visionary or outsider artist, like other self-taught creators who work outside the mainstream and share characteristics such as reclusiveness, mental impairment or extreme eccentricity. He is among the best known practitioners of outsider art, also known as Art Brut, because his sequences of images seemed to many to track the progressive psychological or psychic disintegration that accompanies a ‘descent’ into mental illness.

Here is my profile of Wain, followed by details of the exhibition.

THE PERFECT CAT AND ITS CREATOR

By Tony Thorne

‘The solitary one more real persian cat is the one that is now going to be the one that is the real living animal left alone until the call is given to it at night time this evening … This can be done by giving the call directly the light is seen after the first sleep is over… It is the perfect cat made the more perfect by the willingness given to it.’

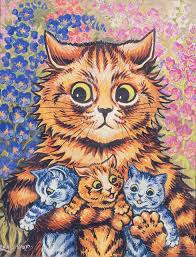

This bizarre text, scribbled on the obverse of a cat portrait, is the work of someone who was once one of England’s most renowned illustrators. Born in London in1860, the artist and visionary Louis Wain travelled a path from obscurity to fame, and back again into seclusion and silence, before his death in 1939 in Napsbury Hospital in Hertfordshire. He was born with a slightly deformed mouth and was kept apart from other children until the age of ten. Even after that the dreamy, distracted boy rarely attended school, preferring to wander around museums and the London dockyards, inhabiting his own private world. He found his vocation at the West London Institute of Art where he studied and for a while taught, before turning to freelance illustration to make his living, beginning with accomplished, naturalistic drawings of birds, dogs, rabbits and fish. When his new wife Emily lay dying of cancer in their home, Louis sat at her bedside and drew her faithful companion, their cat, Peter, and it was these drawings that first caught the public imagination. From 1890 Wain’s cat caricatures, reproduced in magazines like the Illustrated London News and Punch, became a bestselling part of the Edwardian fashion for sentimental pictures of animals, especially dressed as humans and playing human roles, and the artist became a household name.

An early painting, also from 1890, of a group of cats watching a beetle crossing a tablecloth, is both a tour de force of oil technique and, in the intensity of the cats’ quizzical expressions, a faint precursor of future strangeness, (or is this just because we see it with hindsight, knowing what was to become of the artist?)

Louis himself was considered a charming, shy eccentric with an odd, indirect conversational style: he liked particularly to talk of cats’ unusual links with electricity, their sensitivity and intelligence, he tried to interest breeders in developing a spotted variety of cat. He not only depicted cats again and again, acting out fairy-tales, posing in oriental vignettes, impersonating Edwardian gentlemen, in sketches, paintings and book illustrations, on postcards and on keepsakes, to the delight of his new audience, but became a public figure, a champion and patron of the cat as a cherished pet with a life of its own (a late Victorian and Edwardian novelty; previously they had been kept, by men at least, mainly to control vermin). In the decade before World War I Wain was producing up to 600 cat pictures every year; his Louis Wain Annual appeared in 1901, was published every year until 1914, then occasionally up to 1923. ‘English cats that do not look like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves’, pronounced the writer H.G Wells.

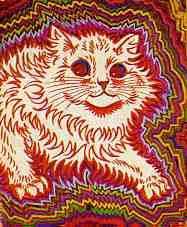

In 1907 Wain’s fame took him to the USA, but, never able to manage money and hopeless at negotiating adequate fees, he returned to London penniless. Not long after this came the first signs of a profound psychic change, and a gradual transformation of the artist’s vision which can be tracked through his later, unpublished works. It is this latter phase of Wain’s working life that has fascinated scholars and members of the medical community. The cats, still playing ball, picnicking, performing on musical instruments, frolicking in gardens, appear more frenzied or ecstatic, their fur electrified, the colours heightened, even livid. Later the titles and printing instructions pencilled on the back of his pictures sometimes mutate into rambling mystical texts, creeping over the page and onto the illustrations themselves.

Wain had spent most of his widowhood living with his five sisters, the youngest of whom, Marie became convinced that she was suffering from leprosy, was witnessing murders, and was certified insane in 1900. Tellingly, in the same year, thirteen years after his wife’s tragic death, Wain recollected that he, she and Peter the cat had formed points on an electric circuit, Emily and the cat acting as batteries. He later imagined that visits to the cinema were robbing his sisters of the electricity which animated them. After Caroline, his eldest sister, died in 1917 Louis’ behaviour became more and more erratic, finally violent. In 1924 he was formally diagnosed as suffering from dementia and placed in a pauper’s ward in Springfield asylum, where the diagnosis was revised to one of schizophrenia. The patient said that he had been ‘bothered by spirits night and day for six years.’ It seemed as if his public had forgotten him, but one year later he was discovered and a campaign by celebrities, including aristocrats, the most eminent authors (Galsworthy and Wells among them) and the prime minister himself, raised thousands of pounds for his care and resulted in him being moved to more pleasant surroundings. While he was incarcerated in the Bethlem Hospital in South London (heir to the infamous Bedlam), Wain made a black-and-white sketch of the hospital exterior, the wards in the background, a solitary cat in the foreground. He presented the drawing as a gift to a visiting clergyman, ‘the cat’, he declared, ‘is me.’

From the early 1920s some abstract tapestry-like patterns had started to appear in Wain’s work, first perhaps recalling the oriental textiles in which his father traded and his mother’s religious embroideries, but becoming more and more spiked and vivid until they begin to invade the foreground, merging with and finally in some cases overwhelming the central images. Possibly better known today than any of the early, conventional works or the jaunty, lovable caricatures is a sequence of five cat portraits, preserved in the Guttman-Maclay archive at the Bethlem museum, that seem to illustrate in the most dramatic way the gradual disintegration of a human personality, a realistic cat morphing into a frenzied apparition before fragmenting into a kaleidoscope of jagged, electrified particles. These images have been reproduced in textbooks and generally taken as visual evidence of mental breakdown, but the truth may be a little more complicated. It’s doubtful that these undated works were completed in the order they are shown and some have tried to claim that they come from very different periods of Wain’s career, (although the staff who nursed him confirmed that they all appeared in the 1930s).

From a conventional viewpoint, Wain may indeed seem a textbook case of schizophrenia, (more recent speculations have included toxoplasmosis and Asperger’s Syndrome) but looked at with a more open mind, his journey can be appreciated in a different way. The gentle, baffled, unworldly outsider comes to identify with the cat for its extreme delicacy and its instinctive, mysterious empathy…and the faint static experienced when stroking its fur becomes an obsession with electrical currents. The distinction between the cat, the self and their surroundings begins to blur. One less orthodox take on so-called schizophrenia is that it is an extreme case of sensitivity and empathy in which the individual personality dissolves, moves beyond our banal human concerns and eventually becomes one with its environment, with all of creation.

During the last period of his life Louis Wain also produced a series of mysterious psychedelic landscapes, part imaginary, partly referencing indirectly real places that he may have known or seen. These scenes usually contain no cats, some depict birds or deer among streams, waterfalls, blossoms and bright coloured leaves, several no living thing at all. In one such work, ‘Ethereal City’, a lone human figure, a tiny man in suit and hat, wheels a trolley through the foreground. Behind him stretch steep hills and deep valleys, more Tibetan than English, with white castellated buildings and walls winding into the distance. Others feature different styles of architecture; mock-Tudor baronial or oriental cupolas. (Wain’s signature on these paintings, incidentally, is clear and firm, identical to those on the early, celebrated productions.)

The late landscapes seem to show a serene, though magically, surreally luminous, world into which the artist himself was disappearing. His visitors in his last years described a peaceful old gentleman, sweeping up leaves or meditating in a deckchair, his agitation and aggression long subsided: still physically inhabiting his quiet institutional home, he perhaps had entered another even more tranquil, idyllic place. As he himself once wrote: ‘I am the origin of nothing I came to the world to try to be the whole of creation I was told the world went round I was told the world went to sleep I awoke to the truth. I was nothing…’

In recent years new generations have rediscovered Wain’s cats – his first posthumous exhibition was in 1972 – and he is once again a celebrated, bestselling artist. Now, though, our appreciation of him must be more complex, taking in the fantastical, unsettling, transcendent hinterland of the cat and its creator along with the charm and enchantment of the wide-eyed, cavorting felines.

Copyright Tony Thorne 2017

Here are details of the current exhibition of Wain’s works, with an excellent review and biography and links to related sites of interest:

https://outsideinpallant.wordpress.com/2017/01/16/the-art-of-louis-wain/