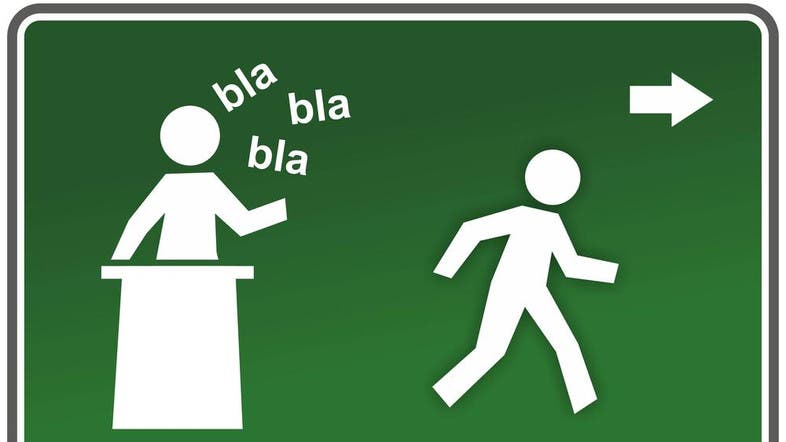

Why do academic professionals masquerade as tongue-tied dullards? In an article a decade ago Tony Thorne demanded a return to donnish wit.

I’ve more than once complained to colleagues that, in the eighteen or so years since I returned to higher education, I have yet to come across an example of ‘high-table wit’. Indeed I’m hard put to recall a single on-campus laugh, let alone a bon mot or jeu d’esprit, in all that time. Colleagues cheerfully riposted that even if there were a High Table, I would be unlikely to be seated at it, and anyway, in a world constrained by critical theory, funding shortfalls and dignity-at-work procedures, what is there to be witty about?

We are hobbled by the mateyness of the tutorial, the robotspeak of the audit culture, not to mention the overemphasis, in Russell Group institutions at least, on mute research, not teaching, as the noblest calling. Levity, in HE, is verboten.

Sophisticated usages, complicated syntax are seen as threats to equal opportunities for the inarticulate. Because we have come to realise that language can disempower, it doesn’t follow that we should muzzle ourselves: if ‘rhetoric’ is widely distrusted as flim-flam and trickery, it doesn’t mean that we should forget its huge (re-)empowering potential.

During one exchange not so long ago a student accused me of having swallowed a dictionary. I not-very-wittily replied that it was probably the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English which I helped edit, but the point is that he was astonished that I dared to strain for eloquence. Many more students have complained to me of the uninspiring delivery of lectures, the numbing aridity of powerpoint-dependent presentations: why, they ask, are their teachers so desperately embracing a geek demotic?

In 1916 the leading literary scholar and writer Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch upbraided those he termed ‘scientific men’, the technocrats of his day, for undervaluing refinement in language, remarking that ‘the sharper the chisel, the more ice it is likely to cut.’ To borrow his (slightly mixed) metaphor, it’s a point well made, and still to the point.

Of course old-style ‘high-table wit’ is an unsustainable cliché, part of a mythology of the academy which is cultivated mainly by those outside it. Who would wish to revive the amusing speech impairments of the poor Reverend Spooner or the effete waspishness of Warden John Sparrow?

The very idea of donnishness – the mystique of the virtuoso lecturer, the unworldly worldliness of the professoriate – is an anachronism, and the tradition of academic witticisms seems to have expired sometime in the 1960s, a decade in which, in Joseph Losey’s film Accident, the acerbic don (Dirk Bogarde) still lived in a sprawling rectory, drove a new Jaguar, and knew all about port.

And yet, and yet… the notion nags at me. I’m really arguing for the sense of self-worth that makes indulgence in humour and the bravura use of language possible, and I guess I’m targeting VCs, VPs as well as practitioners in the humanities, whose rhetorical skills should provide models for their students. Now that the sermon and the debating society are moribund, who else is to take the lead? George Galloway? Stephen Fry? On their own??

Quips around the high table rarely went beyond their immediate audience, but we should be thinking more ambitiously, of a discourse style that can make its user heard above the soundbites and the earnest browbeatings of public debate and restore the right of university teachers to influence opinion on a wider scale

It could be said that this already happens in terms of science and technology, whose public and social influence is unarguable, and there are signs at least that other academic voices are being raised, in the interdisciplinary public debates taking place in London right now for instance, where arts and social science specialists contend with luminaries from the second and third estates.

Let’s pray not just for piety and conviction in those debates, but for repartee and badinage, because the other key component of wit is a sense of humour. Not gallows humour, born of desperation, but what Aristotle defined as ‘cultured insolence’, the byproduct of quick thinking and a keen combativeness; qualities, along with verbal facility, that seem to me to be essential for the survival of a still undervalued and self-effacing academy. Montaigne said wit was a dangerous weapon; in fact it’s not so much the equivalent of Sir Arthur’s little ice-pick as our own sector’s Weapon of Mass Seduction. And it’s time we deployed it.

A version of this article appeared in the Times Higher in September 2006

I have been writing, teaching and broadcasting about new language and linguistic and cultural change for three decades. I have compiled dictionaries and written cultural histories and biographies and founded The Slang and New Language Archive at King’s College London, a resource for scholars, the media and language enthusiasts which I still curate today.

I have been writing, teaching and broadcasting about new language and linguistic and cultural change for three decades. I have compiled dictionaries and written cultural histories and biographies and founded The Slang and New Language Archive at King’s College London, a resource for scholars, the media and language enthusiasts which I still curate today.