more updates on 2025’s language landscape

Once again, I’m very grateful indeed to Randoh Sallihall of Unscramblerer.com for sharing his data on language usage online. I previously posted his analysis of last year’s slang lookups (online searches)* and this time his findings reveal the most popular internet text abbreviation lookups in 2025 so far, for the UK and the USA. I was amused to see SMH (‘shaking my head‘) featuring high in both lists. A few years ago I confidently stated in a BBC radio interview that this stood for ‘same here’ – as I had just been informed by a group of schoolkids. I was immediately and publicly corrected – and shamed – by presenter Anne McElvoy and invited journalist Hannah Jane Parkinson and the bitter experience has stayed with me.** It may be culturally significant also that Britain’s favourite apology – in the form of SOZ – doesn’t feature at all on the American list.

“Analysis of Google search data for 2025 so far reveals the most searched for text abbreviations in the UK.”

Most searched for text abbreviations in the United Kingdom:

1. POV (39 000 searches) – Point of view.

2. SMH (34 000 searches) – Shake my head.

3. PMO (28 000 searches) – Put me on.

4. ICL (17 000 searches) – I Can’t Lie.

5. OG (16 000 searches) – Original gangster.

6. OTP (16 000 searches) – One true pairing.

7. NVM (13 000 searches) – Never mind.

8. TM (11 000 searches)- Talk to me.

9. SN (7 000 searches) – Say nothing.

10. BTW (6 000 searches) – By the way.

11. KMT (6 000 searches) – Kiss my teeth.

12. FS (6 000 searches) – For sure.

13. WYM (6 000 searches) – What you mean.

14. HRU (6 000 searches) – How are you?

15. ATP (5 000 searches) – At this point.

16. SYBAU (5 000 searches) – Shut your b—h ass up.

17. IGHT (5 000 searches) – Alright.

18. ONB (4 000 searches) – On bro.

19. WSP (4 000 searches) – What’s up?

20. TY (4 000 searches) – Thank you.

21. SOZ (3 500 searches) – Sorry.

22. IDC (3 000 searches) – I don’t care.

23. LDAB (3 000 searches) – Let’s do a b-tch.

24. PFP (3 000 searches) – Picture for proof.

25. IBR (3 000 searches) – It’s been real.

26. IYW (3 000 searches) – If you will.

27. TB (2 500 searches) – Text back.

28. FYI (2 500 searches) – For your information.

29. GTFO (2 500 searches) – Get the f–k out.

30. HY (2 000 searches) – Hell yeah.

Most searched for text abbreviations in the United States:

1. FAFO (254 000 searches) – F–k around and find out.

2. SMH (166 000 searches) – Shake my head.

3. PMO (101 000 searches) – Put me on.

4. OTP (95 000 searches) – One true pairing.

5. TBH (93 000 searches) – To be honest.

6. ATP (85 000 searches) – At this point.

7. TS (79 000 searches) – Talk soon.

8. WYF (76 000 searches) – Where are you from.

9. NFS (75 000 searches) – New friends.

10. ASL (65 000 searches) – As hell.

11. POV (63 000 searches) – Point of view.

12. WYLL (59 000 searches) – What you look like.

13. FS (58 000 searches) – For sure.

14. FML (56 000 searches) – F–k my life.

15. DW (55 000 searches) – Don’t worry.

16. HMU (54 000 searches) – Hit me up.

17. ISO (53 000 searches) – In search of.

18. WSG (50 000 searches) – What’s good?

19. IMO (48 000 searches) – In my opinion.

20. MK (45 000 searches) – Mmm, okay.

21. ETA (40 000 searches) – Estimated time of arrival.

22. ICL (37 000 searches) – I Can’t Lie.

23. MB (37 000 searches) – My bad.

24. STG (29 000 searches) – Swear to god.

25. ION (28 000 searches) – In other media.

26. PFP (27 000 searches) – Picture for proof.

27. NTM (27000 searches) – Nothing much.

28. DTM (26 000 searches) – Doing too much.

29. TTM (26 000 searches)- Talk to me.

30. MBN (25 000 searches) – Must be nice.

31. ETC (24 000 searches) – And the rest.

32. BTW (23 000 searches) – By the way.

33. WFH (21 000 searches) – Work from home.

34. GMFU (20 000 searches) – Got me f—-d up.

35. NGL (19000 searches) – Not gonna lie.

36. SYBAU (19 000 searches) – Shut your b—h ass up.

37. BTA (17 000 searches) – But then again.

38. SB (17 000 searches) – Somebody.

39. HBD (16 000 searches) – Happy Birthday.

40. PMG (15 000 searches) – Oh my god.

41. HY (15 000 searches) – Hell yeah.

42. TMB (11 000 searches) – Text me back.

43. WYS (10 000 searches) – Whatever you say.

44. GNG (9 000 searches) – Gang (close friends or family).

45. IKTR (8 000 searches) – I know that’s right.

46. IKR (7 000 searches) – I know, right?

47. ARD (6 000 searches) – Alright.

48. IFG (5 500 searches) – I f—–g guess.

49. HN (4 000 searches) – Hell no.

50. TTH (3 000 searches) – Trying too hard.

A spokesperson for Unscramblerer.com commented on the findings: “Text abbreviations are the secret language of the internet. You could even call them an integral part of social media culture. Snappy, always changing and hard to understand. Texting abbreviations is all about saving time and appearing cool. Keeping up to date with the newest trending abbreviations is no easy task. Old meanings can change while new abbreviations are created. A recent study found that abbreviations might not be as cool as people think. Using abbreviations makes the sender seem less sincere. This also leads to lower engagement and shorter responses. There is nothing wrong with using abbreviations in casual conversations with friends and family. However it is best do draw a line for professional conversations. Context matters.”

Research was conducted by word finding experts at Unscramblerer.com.

We analyzed 01.01.2025 -05.03.2025 search data from Google Trends for terms related to text abbreviations.

Methodology: We used Google Trends to discover the top trending text abbreviations and Ahrefs to find the number of searches. America’s most popular text abbreviations can be discovered in Google Trends through the keyword variations of ‘meaning text’. Abbreviations are used most often on social media and texting. The 2025 top trending abbreviations are the least understood. People have to search for their meaning (example ‘TBH meaning text’). Ahrefs shows many variations of meaning searches like ‘text meaning’ or ‘means in text'(example ‘PMO meaning in text’) and similar keyword combinations(example ‘what does SMH mean in text’). We added up 100 search variations of top text abbreviations.

I was very grateful, too, when Claire Martin-Tellis of content marketing and digital PR specialists North Star Inbound contacted me with an update, again from the USA, on attitudes to outdated slang…

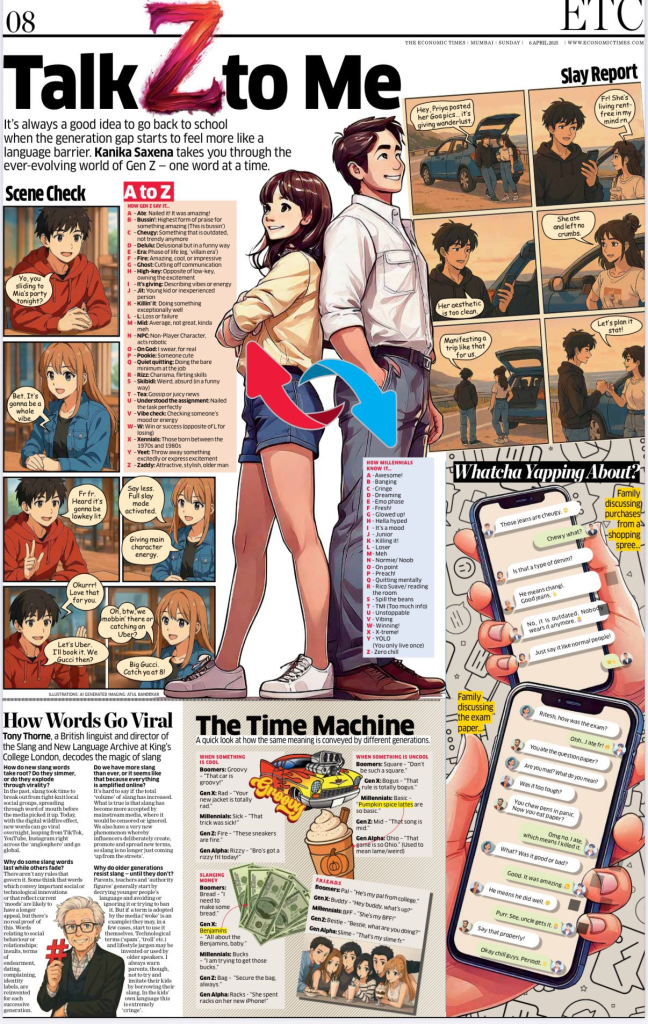

“As new slang terms like “Beta,” “GYAT,” and “Skibidi,” continue to surface, it’s enough even to make Gen Z feel old! Language learning app Preply asked Americans of all ages to weigh in on their favorite era of slang. Here is what decade reigns supreme:

- Over ⅓ of Americans say the 1990s is their favorite decade for slang.

- Men surveyed preferred the 1970s while women preferred the 1990s.

- “Baloney,” “take a chill pill,” and “bogus” are the three most popular slang terms Americans want to see come back.

*https://language-and-innovation.com/2024/11/18/the-search-for-slang/

**the embarrassment is still audible here…https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06vs6g2