Researching and tracking the latest slang can now draw upon statistical analysis of online data.

As 2024 draws to its end and talk among lexicographers, culture journalists and language buffs turns to ‘words of the year’, I’m immensely grateful to Randoh Sallihall of Unscramblerer for providing me with his datasets showing lookups (Google searches) for the most popular recent slang expressions…

Most searched for slang words in United Kingdom:

1. Gaslighting (170 000 searches) – a type of manipulation that makes you doubt your memories and feelings. The person doing it may lie and deny things.

2. Skibidi (125 000 searches) – refers to a viral internet trend featuring surreal, animated videos of singing toilets and dancing heads, popularized on platforms like TikTok for its bizarre humor.

3. Pookie (47 000 searches) – to show endearment and affection. Used for a close friend, partner or family member. A playful way to say someone is special.

4. Hawk tuah (40 000 searches) – imitative of a spitting sound. The catchphrase originates from a viral street interview conducted in June 2024 with Haliey Welch, who stated that her signature move for making a man ‘go crazy’ in bed was to ‘give him that hawk tuah and spit on that thang’.

5. Sigma (37 000 searches) – refers to an independent, self-reliant person who operates outside traditional social hierarchies, often described as a ‘lone wolf.’

6. SMH (31 000 searches) – internet slang for ‘shaking my head’. Used to express disapproval or disappointment.

7. Demure (26 000 searches) – reserved, modest or shy in manner or appearance. The TikTok user Jools Lebron made a series of viral videos using the phrase “very demure”. This trend gave the word a playful slang meaning. She uses it to assess appropriate makeup and fashion choices in various settings.

8. Rizz (25 000 searches) – style, charm or attractiveness. The ability to attract a romantic partner and make others like you.

9. Dei (17 000 searches) – diversity, equity, inclusion. A family friendly way of saying woke.

10. Aura (13 000 searches) – the vibe someone gives off. When used by tweens and teens it is likely a reference to how badass someone is. Aura points make you cooler. So you definitely want to earn more aura points instead of losing them.

We can compare this list with Randoh’s equivalent for the USA, used in the Newsweek article posted previously to which I contributed, and reproduced here with his explanatory comments…

Analysis of Google search data for 2024 reveals the most searched for slang words in America:

1. Demure (260 000 searches) – reserved, modest or shy in manner or appearance. The TikTok user Jools Lebron made a series of viral videos using the phrase “very demure”. This trend gave the word a playful slang meaning. She uses it to assess appropriate makeup and fashion choices in various settings.

2. Sigma (220 000 searches) – refers to an independent, self-reliant person who operates outside traditional social hierarchies, often described as a ‘lone wolf.’

3. Skibidi (205 000 searches) – refers to a viral internet trend featuring surreal, animated videos of singing toilets and dancing heads, popularized on platforms like TikTok for its bizarre humor.

4. Hawk tuah (180 000 searches) – imitative of a spitting sound. The catchphrase originates from a viral street interview conducted in June 2024 with Haliey Welch, who stated that her signature move for making a man ‘go crazy’ in bed was to ‘give him that hawk tuah and spit on that thang’.

5. Sobriquet (105 000 searches) – a nickname or descriptive name given to a person or thing. Borrowed from French sobriquet (nickname).

6. Schmaltz (65 000 searches) – refers to excessive sentimentality or melodrama. Often used for art, movies, music or storytelling if there is too much sappiness.

7. Sen (50 000 searches) – slang for self.

8. Katz (34 000 searches) – a term for anything enjoyable, fun or pleasing. It can also mean ‘yes’.

9. Oeuvre (25 000 searches) – refers to the complete works produced by an artist, writer or composer. A word used by literature professors to express superiority.

10. Preen (20 000 searches) – slang for a child who tries to act like a teenager(wears teen clothes or makeup).

A spokesperson for Unscramblerer.com commented on the findings: “The English language is ever changing. Every year new slang words are created. Many slang words are born through trending topics and viral videos on social media. However only few manage to stick around long enough to be added to the dictionary and remain in daily use. Slang words are a normal and fun evolution of language. We encourage everyone to learn some new words and surprise their children by using them.”

Research was conducted by word-finding experts at Unscramblerer.com.

We analyzed 01.01.2024 -25.10.2024 search data from Google Trends for terms related to slang words.

Methodology: We used Google Trends to discover the top trending slang terms and Ahrefs to find the number of searches. Americas most popular slang terms can be discovered in Google Trends through the keyword ‘meaning’. People will hear or read slang terms and search for the meaning of the term (example ‘demure meaning’). Ahrefs shows many variations of meaning searches like ‘slang’ or ‘trend’ (example ‘demure slang’) and similar keyword combinations (example ‘what does demure mean’). We added up 150 search variations of top slang terms.

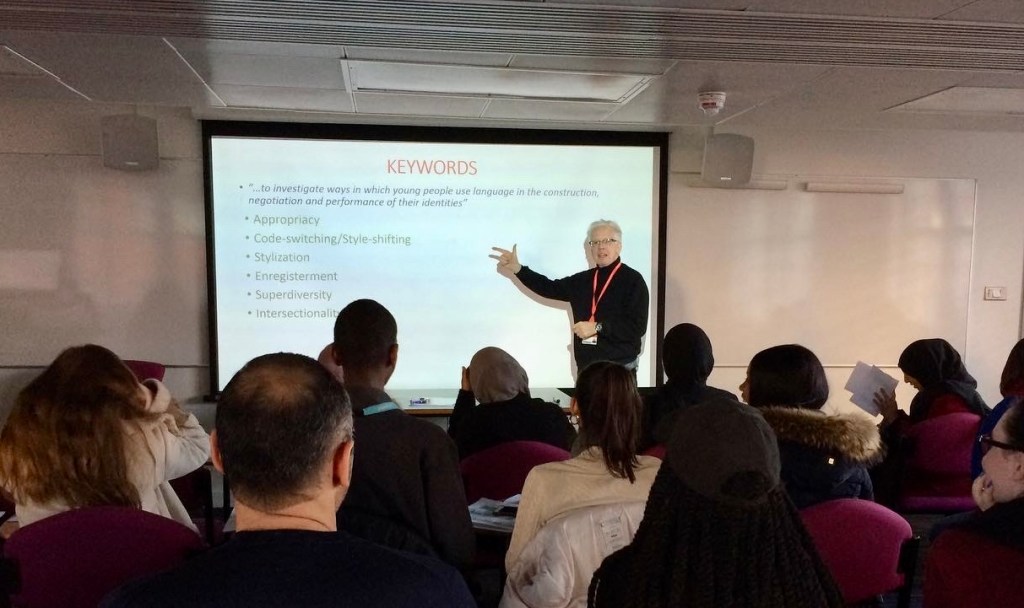

A few days after Randoh’s findings were published, I was asked by Robert Milazzo* to take part in the masterclass on new slang and youth language that he convened at Virginia Commonwealth University. The whole lively one-hour event was recorded and can be accessed here…

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1yYlV7LkKdEf5AqFF-bJQAfIE5s5PUpGi/view?usp=sharing

Robert’s class was particularly illuminating, allowing as it did for contributions from young slang users themselves and from puzzled old-timers too. Bear in mind that the samples handled by data analysts are taken solely from online usage and not from authentic speech. Nearly all the slang used on TikTok, YouTube, Instagram, etc. originates in the USA whereas the slang terms used by British youth in their IRL conversations will differ considerably from their North American counterparts, showing much greater influence from African Caribbean rather than African American sources.

*https://www.linkedin.com/in/robert-milazzo-3a8860116/