The Autumn Equinox, and time for the latest perspectives on slang and youth language in the Anglosphere…

I‘m very grateful indeed for the latest data on the most popular slang terms – according to online searches – among younger people in the USA, provided once again by Randoh Sallihall of Unscramblerer.com…

Most searched for slang words in America:

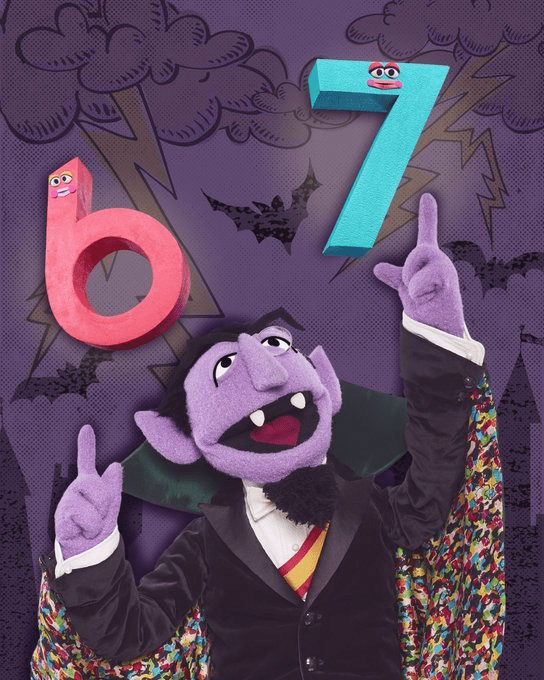

1. 6-7 (141 000 searches) – There is no literal meaning to six seven. Its absurdity is the point, making it a prime example of “brainrot” internet humor where the randomness itself becomes funny. It originates from the song “Doot Doot (6 7)” by Skrilla. LaMelo Ball a basketball player created a trending video about being 6 feet 7 inches tall using the song. Kids and teens scream and chant it often paired with exaggerated hand gestures. *See also below

2. Bop (115 000 searches) – A person with many sexual partners (bops around from person to person). Someone who presents oneself online in a way that is thought of as immodest. A derogatory word often used in cyberbullying.

3. Mogging (79 000 searches) – outclassing someone else by appearing more attractive, skillful or successful. Looksmaxxing (16 000 searches) has a similar meaning that is also a trending slang word this year.

4. Huzz (61 000 searches) – refers to attractive girl or a group of girls. A replacement for ‘boo’ and ‘pookie’. Somebody you want to impress. This slang had a more derogatory meaning ‘h–s’, but that has changed.

5. Chopped (59 000 searches) – this term has become a synonym for something that is ugly, undesirable or unattractive.

6. Big back (57 000 searches) – refers to someone with a large physique. Someone who is seen as gluttonous or out of shape. It’s less about literal size and more about poking fun at behavior, like hogging food or being sluggish.

7. Glazing (49 000 searches) – means to praise someone excessively and insincerely. A way to call out behavior where excessive flattery is used.

8. Zesty (44 000 searches) – someone who is lively, exciting or energetic.

9. Fanum tax (36 000 searches) – playfully taking a portion of a friend’s food. The streamer Fanum began this trend.

10. Green FN (34 000 searches) – refers to a guaranteed win. Describes something amazing and highly desirable. Often said after an exceptional shot or throw in basketball. The term originates from the NBA 2K video game series, where a perfectly timed shot is marked by the color green.

11. Delulu (32 000 searches) – short for delusional. It describes someone with unrealistic expectations, especially about crushes, relationships, or fantasies (thinking a celebrity will date them).

12. Clanker (29 000 searches) – is a derogatory term for robots and AI technology. An example would be “having to talk to a clanker” would mean talking with a chat bot.

13. Ohio (24 000 searches) – refers to anything that is strange or absurd.

14. Slop (21 000 searches) – describes low effort AI generated content.

15. Aura farming (18 000 searches) -refers to a behavior (often referencing anime characters) where a person does something for the sake of looking cool.

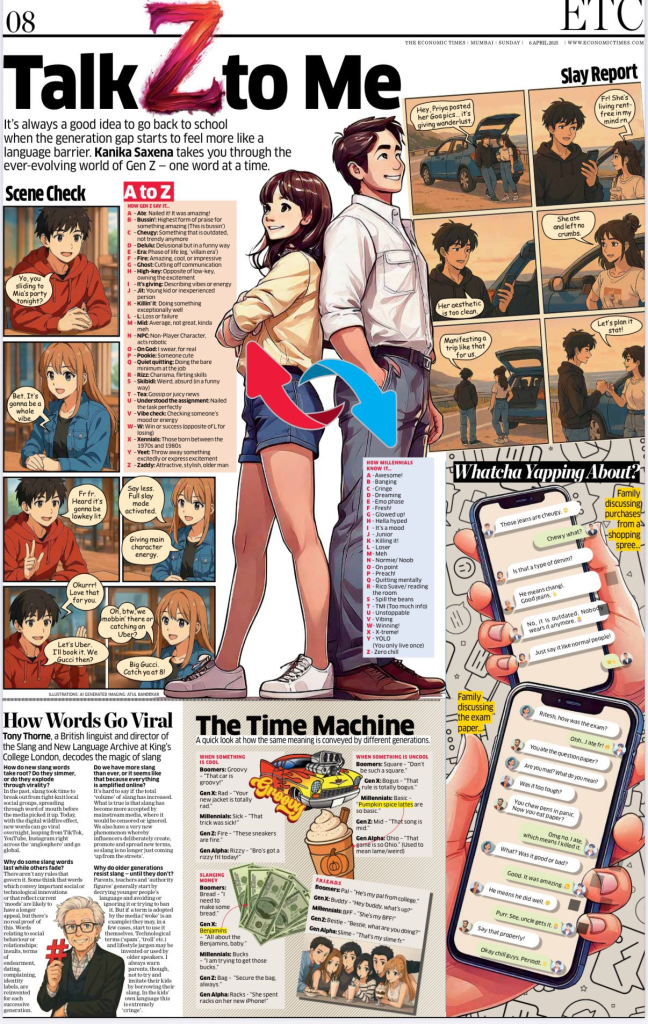

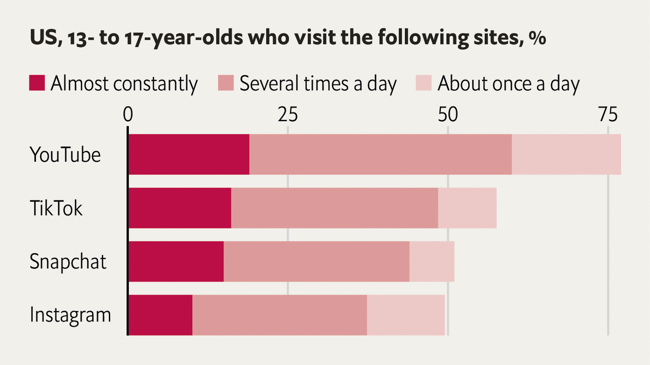

A spokesperson for Unscramblerer.com commented on the findings: “Popular slang in 2025 continues to be heavily influenced by TikTok, Instagram, gaming, streaming, Gen Z and Alpha online communities. Trends from social media spread rapidly via memes and viral challenges. Fueled by technology our language adapts to new slang trends more rapidly than ever. Slang is a fascinating and fun mirror of our culture.”

Research was conducted by word finding experts at Unscramblerer.com.

We analyzed 01.01.2025 -19.09.2025 search data from Google Trends for terms related to slang words.

Methodology: We used Google Trends to discover the top trending slang terms and Ahrefs to find the number of searches. Americas most popular slang terms can be discovered in Google Trends through the keyword ‘meaning’. People will hear or read slang terms and search for the meaning of the term (example ‘mogging meaning’). Ahrefs shows many variations of meaning searches like ‘slang’ or ‘trend’ (example ‘mogging slang’) and similar keyword combinations (example ‘ what does demure mean’). We added up 150 search variations of top slang terms.

The words recorded in the US can be compared with this list of slang collected in UK schools by Teacher Tapp in August…

https://teachertapp.com/uk/articles/down-with-the-kids-slang-in-british-classrooms-2025/

Earlier this month I spoke to Avantika Bhuyan, Editor at India’s Mint Lounge magazine, about the youngest online cohort, Gen Alpha. She asked me how their interactions with technology and language differed from their predecessors…

Gen Alpha are of course the first generational cohort to have grown up wholly surrounded by digital technology, digital media and the online culture that accompanies them. They are adept at using the hardware – mobile phones, tablets, gaming gadgets – but also unlikely to be dazzled by these already dated mechanical devices. They have sometimes returned to old fashioned film cameras and Polaroids, wind-up watches, puzzles and pinballs as interesting relics (something which in older users is described by theorists as ‘haptic nostalgia’. For them AI isn’t a terrifying threat but just part of the digital landscape they navigate daily.

Gen Alpha are active on YouTube (short-form video by preference), Instagram and – especially – TikTok where they can participate and emulate, or react to influencers and content-creators and individual TikTok celebrities, This media reinforces accelerated performances, exaggerated poses and a pervading sense of self-consciousness, self-mockery, irony and absurdist humour, prompted partly by their collective anxiety at being on display, surveilled and judged 24/7.

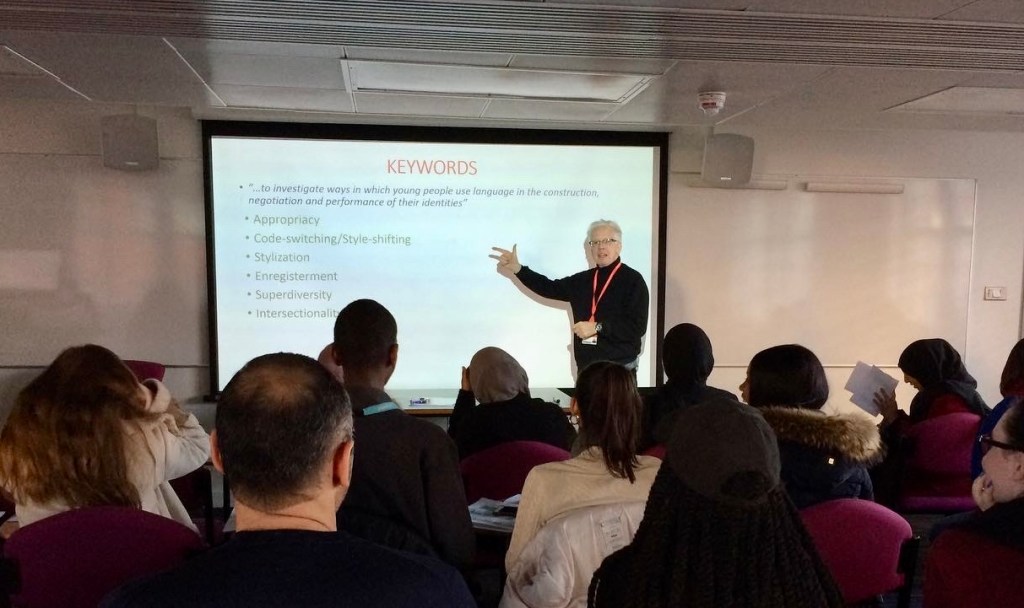

Gen Alpha slang, like GenZ’s differs from that of older generations in that it’s not just language that arises ‘naturally’, escaping from the streets or disseminated by movies, TV and the music industry. The language they use has often been generated deliberately by techbros, influencers and microcelebrities who are not just trying to communicate but to gain prestige, kudos. The slang they use also differs from older versions in ways which are interesting to linguists like me: the ‘words’ are not just words but operate virally like memes and, like memes, they are ‘multimodal’, made up not just of writing or sounds like traditional words but accompanied by images, sound effects, references to other messages, in-jokes, puns, etc.

Older generations often find Gen Alpha’s vocabulary baffling, ridiculous or annoying – unsurprisingly since the language is used in part to project behaviour and values that are alien to parents, teachers. Key words – such as ‘skibidi’ – may actually be meaningless, more comic gestures than information-bearers and the passing visual fads and fashions that Gen Alpha (and Gen Z) indulge in – microtrends and looks and what they call ‘aesthetics’ or ‘vibes’- are not designed to last.

There may be serious effects to these innovations and new behaviours. Dating is much more fraught, more competitive when its potentially being exposed globally, and partners’ motives may be even more conflicted, contradictory and mutable when the rituals of romance are playing out in an environment already disrupted by older generations’ repertoire of ‘ghosting’, ‘gaslighting’, ‘benching’ and ‘breadcrumbing’.

Above all we older people mustn’t underestimate Gen Alpha. They may sometimes be victims of the toxic aspects of digital culture, but they are also adept at coming to terms with it, manipulating it to their own advantage – or knowing when to reject it.

Avantika’s long feature on Gen Alpha is here…

Another way in which mainly younger creators and communicators are changing language is by way of Algospeak, the online code used to disguise messages and evade surveillance…

*In October I spoke to BBC Radio London about the phrase ‘six seven‘ (number one lookup in the US, above) which had now come to the attention of British media, having crossed over from TikTok performances and online posting to real-life irritation of UK teachers and parents. The meaningless phrase, unrelated to the very old expression ‘at sixes and sevens’ (in a state of confusion or disorder) which was used by Chaucer and Shakespeare, was being chanted with accompanying gestures (outstretched arms, palms upward) to tease, baffle and mock adults. Its young users were possibly unaware of its origins in the lyrics of a rap track by US artist Skrilla and its subsequent adoption by basketball stars and their followers.

Nobody as far as I know has yet mentioned – as my friend Nicky Hill reminded me – that the same numbers were already in use in South London in a more sinister context…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/67_(group)

And, also on Twitter, from Celandine an intriguing tangential suggestion…

‘I saw something suggesting that parents take the opportunity to cite Deuteronomy 6:7! “You shall teach them (the Commandments) diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise.”’

On the eve of All Hallows Eve the Guardian continued the narrative…

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/oct/30/six-seven-meaning-slang

And for those who remember…

In November I was interviewed by Laura Cannon for BBC Bitesize, again about viral slang and trending youth language and its implications. Laura’s article is here…

6-7 and the ‘secret’ language of kids – BBC Bitesize

In December Dazed magazine featured its recommendations for Christmas gifts alongside a list of the year’s archetypes – the new identities which have replaced or reinforced the aesthetics, vibes and microtrends of 2024…