youth slang crosses world englishes

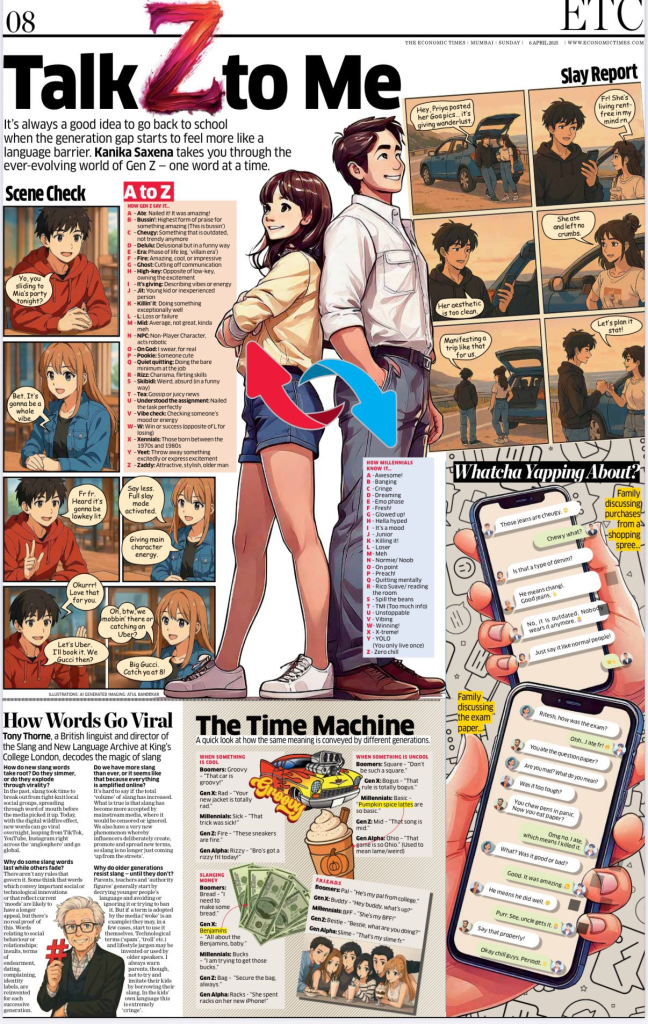

Last week I was interviewed by two young journalists about the pervasive slang generated by Gen Z and Gen Alpha. Interestingly both journalists are operating outside the US/UK matrix from which much of this language variety emanates. Interestingly too, both journalists asked similar questions about the latest linguistic novelties and how we might respond to them. Kanika Saxena‘s piece appeared in the Economic Times of India, and my contribution is here…

1. How do new slang words take root in a generation? Do they slowly build momentum, or does one viral moment suddenly put them everywhere?

In the past it could take some time for slang to escape from the local social group (‘in-group’ or ‘peer group’: a group of friends, a gang, fellow workers, etc.) where it originates into the outside world, then to spread by word of mouth into other parts of society, finally perhaps being picked up by the entertainment or print media. Nowadays this process has been massively speeded up by messaging and the internet, so that a novel term can go viral and reach beyond its original community almost instantaneously. New expressions can spread via social media and platforms like TikTok, Youtube, InstaGram right across the ‘anglosphere’ and go global.

2. Some words stick around for decades, while others vanish overnight. What makes certain slang words stand the test of time?

Linguists have tried to analyse why some terms become briefly fashionable and then disappear while others endure. There don’t seem to be any rules that govern why this happens. Some experts think that words which convey important social or technological innovations or that reflect current ‘moods’ or preoccupations are likely to have a longer appeal, but there’s no real proof of this. It could also be because a word relates to important social behaviour or relationships: insults, terms of endearment, ‘dating’ language, complaining, identity labels, for example, have to be reinvented for each successive generation, then persist until their users mature or grow older.

3. With social media throwing new words at us daily, are we actually creating more slang than before, or does it just feel that way because everything is amplified online?

It’s hard to say if the total ‘volume’ of slang has increased because, in the past at least, it was impossible to quantify it. What is definitely true is that slang has for some time become more accepted by mainstream media whereas it used to be censored or ignored. We also have the very new phenomenon whereby influencers, TikTok stars and content creators are using online resources to consciously, deliberately create, promote and spread new terms, so slang is no longer just coming ‘up from the streets’ (or spread via music, TV and movies) but is a commodity exchanged and pushed to gain prestige or sell oneself.

4. Older generations always seem skeptical of new slang—until, of course, they start using it too. What’s the secret to a word crossing generational lines?

Parents, teachers and ‘authority figures’ generally start by decrying younger people’s language and avoiding or ignoring it or trying to ban it. (This isn’t really justified by the way: slang may be seen as socially marginal but is not technically deficient or defective language and uses the same techniques as poetry or literature) But if a term is adopted by the media (‘woke’ is an example) they may in a few cases start to use it themselves. Technological terms (‘spam’, ‘troll’ etc.) and lifestyle jargon may be invented or used by older speakers. I always warn parents, though, not to try and imitate their kids by borrowing their slang. In the kids’ own language this is extremely ‘cringe’.

My second interview was with Austėja Zokaitė who is based in Lithuania and it appears in the online magazine Bored Panda, an arresting and anarchic daily roundup of the latest viral images, memes and commentary on internet culture. The whole report is here, with my comments interspersed with the succession of visual elements…

This IG Page Shares “Hard” Images, And Here’s 30 Of The Most Unhinged

Two weeks later I took part in a podcast on the subject of Slang, hosted by US students Sophie Xie and Andrea Lee. Our discussion is here…