Creative incoherence – human and penguin

Twenty years ago I wrote about the intriguing imaginary ‘language’ spoken by the much loved cartoon character Pingu, a charming animated penguin. In August 2024, in a short but comprehensive video documentary, France Culture reviewed almost the entire history of the creative use of gibberish (in French ‘charabia‘), also known as ‘Grammelot’ or ‘Macaronic Language’, in performances on stage, in public, in poetry and on film and video. Producer Alexis Magnaval asked me to contribute and the result is here…

L’art du charabia, de la Commedia dell’Arte à Pingu (youtube.com)

My original article is here…

Pingu’s Lingo, or How to Get By in Penguinese

Tony Thorne

Pingu the penguin, his baby sister Pinga and the rest of the creatures who share his TV adventures also share a very special way of communicating with each other and with us. They talk in ‘Penguinese’, a wonderfully expressive and mysterious language which captivates kids and fascinates grown-ups, too. It’s partly due to this Pingu-talk that the tiny cult figure has established a worldwide following – some of Pingu’s many teenage and student fans even use Penguinese in their own conversations.

Other kids’ favourites like Sooty’s companion Sweep, Bill and Ben the Flowerpot Men, the Clangers and the Teletubbies, all have their own very different ways of ‘speaking’, but charming as they are none of these really amounts to a language. From a linguist’s point of view Sweep’s squeaks imitate the main syllables of just a few key words, while Bill and Bens’ conversation, officially dubbed ‘oddle-poddle’, but known to kids by their trademark cry of ‘flobadob’, consists of sequences of burbling which occasionally throw up a mangled but recognisable English phrase. The Clangers’ whistles disguised a script which their creator Oliver Postgate admitted was full of swearing, and the Teletubbies imitate the limited range of almost-words of very young children. Of all the languages created for children’s characters, one stands out from the rest – and of course that one is Penguinese.

Carlo Bonomi, the Italian character actor who originally created Pingu’s voice says that ever since he was a child he has been entertaining himself by inventing make-believe languages and experimenting with amusing noises. In other words Bonomi has a lifetime of practice behind him which helps explain the gift that he is now so modest about. According to Bonomi there is also a long tradition in France and Italy of clowns and travelling players using nonsense language, and their special technique for suggesting character through abstract noises, called Gramelot, from an old French word for muttering or murmuring, has also influenced him in creating Penguinese. Carlo claims that any trained actor could do what he does, but this plainly isn’t true. It’s actually almost impossible to speak for long in a made-up language – try it yourself! What usually happens when you attempt to improvise is that after a few seconds you either lapse into real speech or you begin to repeat the same sounds at regular intervals. The next voice artist to take on the Pingu challenge has got an extremely hard act to follow.

It’s a feature of the most sophisticated imaginary languages that when you listen to them, you think you hear words you recognise. Everyone has an opinion on where Pingu’s language comes from: at various times it has been claimed that it contains bits of Icelandic, Finnish or Italian. Knowing that the series originated in Switzerland has led some people to assume that it’s Swiss-German dialect that he’s using. Many self-styled experts will assure you that its sounds are clearly based on the rhythms of European languages – one of the few identifiable words,’ca-ca’, for ‘poo’, is part of baby-talk in most countries in Europe – but Pingu fans in Japan are convinced that he is speaking their language at least some of the time, and one website for Pingu fans announced recently that the secret is out – Penguinese is based on Swahili! It isn’t. The truth is that it is a language all its own, and for that reason it is able to cross all language barriers and to appeal to everyone.

Critics used to complain that ‘gobbledygook’ languages would damage children’s own speech development, but experts now think that this is false (after all, imitating Donald Duck never did anyone any lasting harm). Language specialists today think that hearing strange languages stimulates children, who soon come to understand how voices are used for comic effect and learn to appreciate the emotional resonance of sounds. In the case of Penguinese the very fact that the ‘speech’ is made up of abstract noises helps young viewers to concentrate on action and feeling.

The study of sounds is known as phonology, and analysing the sounds Pingu makes reveals why he is such a good communicator. Penguinese has a complex intonation pattern – intonation is the ‘music’ of speech with its changes of pitch and tone, its rise and fall. It seems to mimic not just the languages of human beings, but the sounds that animals – and birds of course – make, too. Other features which testify to its authentic effects are the fact that longer stretches of dialogue speed up and slow down just as they do in the real world, and pauses and hesitations mark out the meaning-sequences that are represented by sentences in nearly all languages.

Linguists have long understood that total communication is not only about noise, but also involves facial expression, gesture and movement; all the subtle and not-so-subtle methods we have for getting across a message are used together. Pingu’s speech is so rich because it consists not only of a wide range of different sounds, but of the body language that goes with them.

The structure of real language is made up of syntax – the stringing together of parts of speech, nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc. in a particular order, and lexis, our vocabulary, or the stock of words we choose from. Even though we can’t be sure that we can identify all the details, we can sense that there is a similar pattern to Pingu’s language, in which some key features recur. Pingu’s fans have collected lists of some of his favourite sounds and gestures, foremost among them the flipper-flapping, wide eyes and squeaking sound that when they are combined indicate alarm, or the trumpet-shaped beak and the ‘meck-meck’ which he uses to announce his arrival. There is also the flipper over the beak and the ‘hoo-hoo’ sound of evil sniggering which is associated with misbehaving. Other characteristic noises include whining, laughing, murmuring agreement, whistling with boredom, impatient snorting and more bizarrely, yodelling.

For language-buffs even Pingu’s name is intriguing. Although real-life penguins come from the Antarctic, in the Southern Hemisphere, Pingu and his family live in an Igloo, an ice-house found only in the Arctic. By a strange coincidence the Inuits (Eskimos) who invented the igloo have the word pingu in their language. It means a conical mound or bank of ice. Far more likely of course that our hero’s name is inspired by ‘penguin’, or its equivalents in German, Pinguin, or Italian, pinguino. Nobody has yet suggested that Pingu is Welsh, but penguin was, it is claimed, originally pen gwyn, Welsh for ‘white top’, referring originally not to penguins at all but to the snow-capped islands where auks -another species of seabird -used to live.

Perhaps the last word on Pingu’s unique language should go to a Japanese fan who recently wrote on the Internet that in a world whose media is dominated by big powerful languages like American English and Japanese, it’s the fact that Pingu doesn’t speak those languages that allows everyone everywhere to feel that he belongs to them. The fan went further, ‘the heartfelt voices of Pingu and the other characters have a magical power, communicating true feelings and friendship’.

Tony Thorne is Director of the Language Centre at King’s College, University of London. He speaks four languages well, another six badly, and is only a beginner in Penguinese.

© Copyright Tony Thorne 2004

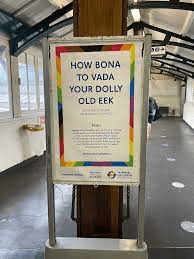

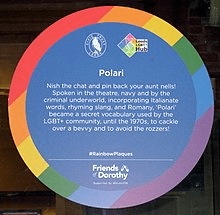

In August I also contributed to another article describing a colourful and playful secret language of evasion, complicity and mockery. This time the underground gay and theatrical code polari, analysed here for Geo France – in French – by Eva Mordacq