‘I am a poor man, but I would gladly give ten shillings

To find out who sent me the insulting Christmas card

I received this morning.’

George Grossmith – The Diary of a Nobody

The tradition of sending Christmas cards by post has declined, though in a 2017 survey British respondents said they still preferred paper to texts or emails, while self-styled experts on etiquette dismiss the electronic ‘card’ as vulgar. Most of the cards I receive now come from charities soliciting donations or estate agents promoting retirement homes, nevertheless…

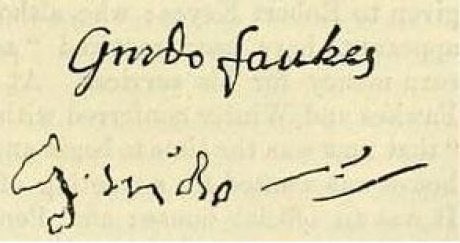

Sole example of a proto-Christmas card, a Rosicrucian manuscript on folded paper, decorated with a rose-sceptre, was presented to King James VI of Scotland and I of England at Christmas in 1611. It was inscribed as follows…

‘…a gesture of joyful celebration of the Birthday of the Lord, in most joy and fortune, we enter into the new auspicious year 1612. Dedicated and consecrated with humble service and submission, from Michael Maier, German, Count Palatine, Doctor of Medicine and Philosophy, Knight and Poet Laureate…’

Joy comes via Middle English from Old French joie, which could mean joy or jewel, itself from Latin gaudia, gaudium, from Proto-IndoEuropean *geh₂widéh₁yeti, from the verb *geh₂u– , to rejoice.

Glad tidings combines the Old English word for bright or cheerful, from an Old Germanic term for smooth, with the Old English and Old Norse words for happenings, occurrences, tidung and tiðendi , which derive ultimately from the IndoEuropean root *di-ti, meaning divide, as into time-frames. The -tide of Christmastide or Yuletide has the same source.

Noel was nowel in Middle English, an anglicisation of French noël, from Latin natalis, shorthand for birthday. Latin nātīvitās, birth, became Old English Nātiuiteð, one of the earliest names for Christmas, and gives us modern nativity.

A particular favourite, thought for several centuries to describe an essence of Englishness, is of course Merry

- joyous, cheery, gleeful, of good spirit

- mirthful, convivial, affected by gaiety, as by festive spirit

- Colloq tiddly, squiffy, somewhat inebriated, as if by seasonal spirits

ME merye, from OE myrige, delightful, pleasing, sweet, from Proto-Germanic *murg(i)jaz, fleeting, from Proto-IndoEuropean *mreg(h)us,short

- make merry behave in a frolicsome, boisterous, unconstrained manner, eg dad-dancing, shattering wine-glasses during toasts, communal bellowing of sentimental songs, flirting at the office party (syn: ‘attempting to pull a cracker’) etc.

- Slang merry-bout an act of copulation (1780) merry-got a bastard (1785) merry-legs a harlot (19C) merry old soul an arsehole (20C rhyming)