Teen talk continues to baffle older cohorts, but as autumn approaches the vibes shift – and Tiktok identities evolve…

In mid-August I talked to Mary McCarthy about the ever-changing patterns of youth language, and, with her kind permission, Mary’s article for the Irish Independent follows…

No cap, sigma and rizz? You’ll need more than Google Translate for teen talk now

Parents are supposed to be bemused by the slang words their children use, but the new summer vocab in our house has me totally flummoxed. This is particularly so with the younger two lads – eight and 11 – who walk around saying nonsense words like “sigma”, “no cap” “Skibidi Toilet” and “gyat” all the time.

I don’t mind them having in-jokes, and it’s nice to see them falling around laughing – I’ll take that over sullen moods any day. But what are they laughing about?

Are they being kind? I can see the pleasure of getting the giggles over absurd stuff. I used to have this thing with a school friend where we would say repeatedly “The dog is dead” in a Northern Ireland accent – no idea why. But there is so much coming at them now online. How can I know they won’t soak up the wrong messages? The Andrew Tate alpha-male rubbish, for example.

This week I hired my Gen Z 16-year-old to help me decode what his brothers were saying, and he pocketed his €5 before unhelpfully telling me that “it’s just little kids saying random, mental stuff”.

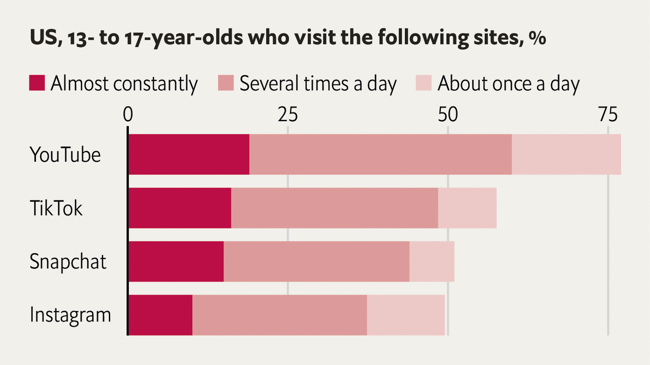

“It’s the internet, it’s TikTok language,” he said. But they don’t have TikTok, I reminded him. YouTube shorts are the same and they have a lot of that, he told me darkly.

So I asked the lads themselves, and they were fairly keen to enlighten me, which was reassuring. “No cap” means no lying, “sigma” just means cool (no Andrew Tate alpha-male link, thank goodness) and rizz is “charisma”.

My 11-year-old elaborated. “So, this would be a chat-up line like, ‘Are you from Tennessee? Because you’re the only ten I see’.” I’m unsure what to say. They refused to explain “gyat”, so I looked it up later.

It mostly seems fine. They’re getting it from pals and YouTube shorts, which I will limit more now. But what I’m most baffled about is the Skibidi Toilet YouTube show, and why they call everything Skibidi for no reason.

The show has amassed over 65 billion views over the last year, and I can’t see any pull factor. It’s about toilets with human heads engaged in a war with people who have CCTV cameras for heads, all set in a dystopian landscape. Apparently, there will be a TV show and a movie. I had a headache watching it after 30 seconds.

Youth slang can spread very quickly these days via online platforms and messaging

It’s everywhere. We were on holiday in Kerry a few weeks ago and had a few hours to kill in Kenmare, so we visited the Kenmare Stone Circle, which was erected some time between 2000 and 500 BC. If you clip a wish at the Hawthorn Fairy Tree, it comes true. That’s according to the man working there, who handed us a piece of paper and a pen.

Being my nosy self, I immediately started reading other people’s wishes, and among the pleas for health, happiness and planning permission there were lots of Skibidi.

“Sigma, sigma on the wall, who is the Skibiest of them all?” one card read.

“Desidere che i cani diventine Skibidy Toilet,” read another, which Google translate told me was “Wish that dogs become Skibidy toilets” in Italian. So it’s not just my children larking around. I’m sure it’s all just a silly phase, perhaps the same as my own “the dog is dead”.

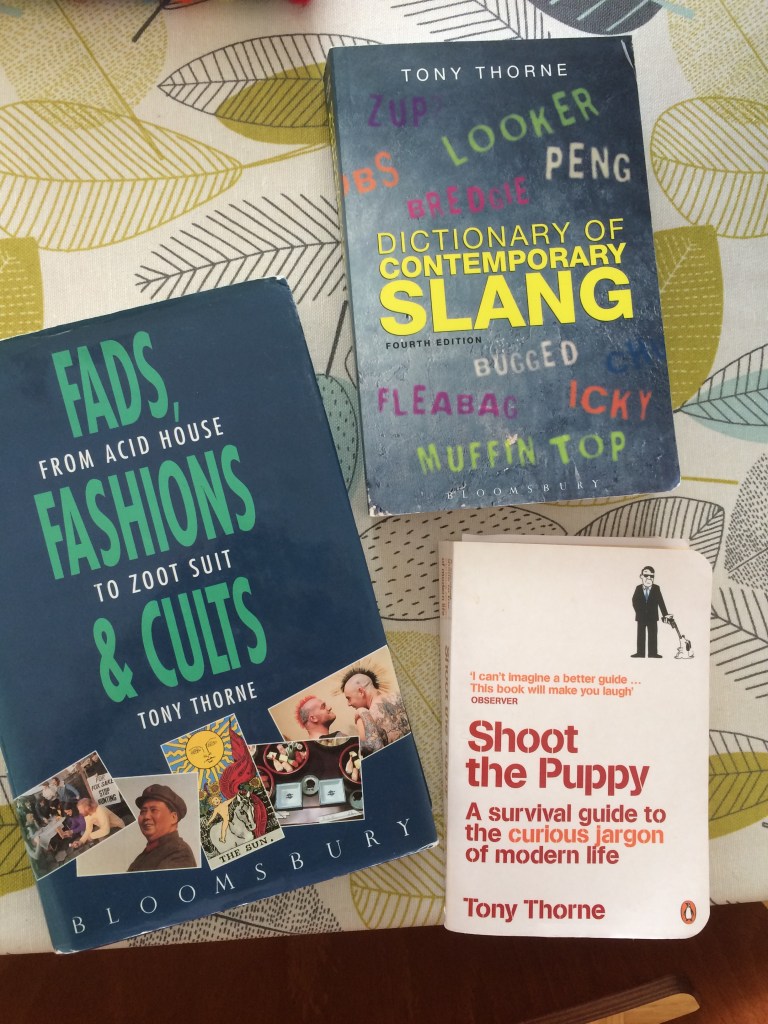

Tony Thorne, director of the Slang and New Language Archive at King’s College London, said young people have always created their own language to keep outsiders like parents and teachers out. It just happens that there’s more around today.

“This language innovation, as linguists call it, used to take place in private spaces and only sometimes spread further – if, for example, the language was used in music or movies or TV comedies,” he said.

“Youth slang can spread very quickly these days via online platforms and messaging and so can become global. Terms often coined in the US rapidly move into the Anglosphere. We see that in the huge network of English speakers who converse excitedly in ‘mid-Atlantic’ accents.”

Thorne recommends the guide to teenage slang on the Gabb.com website. I soon discovered that “gyat” is a way to express admiration, usually for a woman’s backside. So I nipped that one in the bud.

It is a habit for parents and the older generation to laugh at teenagers for speaking in a frivolous way

Once you start researching the origins of these words, it gets interesting. According to a recent Forbes article on how Gen Z language is changing the workplace, to “slay” – which is something my 13-year-old daughter says, as in “You slayed that lasagne, Mammy” – means “high praise” and originated in black and LGBTQ+ communities before gaining popularity on TikTok.

I can’t remember using much slang as a teen, apart from the many violent descriptions we had for being drunk, among them flutered, slaughtered, battered and trollied.

My cousin would visit from Canada, and she loved hearing those terms. Today, though, there’s no difference between what a 15-year-old in Dublin and a 15-year-old in Toronto is exposed to, and they’re the more creative for this. After all, the way we learn to speak is from listening to other people, so we probably don’t really need to worry much about the slang.

Kevin Barry, former professor of English at the University of Galway, said that while adults can see it as foolish, there’s a wisdom to the newly minted words and phrases.

“It is a habit for parents and the older generation to laugh at teenagers for speaking in a frivolous way – to the adults it makes no sense. What they are seeing is the frontier of language change, which is a creative Wild West,” he said.

There’s no point trying to keep up. New slang will be coined as fast as I learn. We can’t police it. The only thing to do is role-model IRL (in real life) what it is to be a nice person. To not shout, to be kind, to make time for the children. To let them know you have high expectations for their behaviour by having high expectations for your own – no cap.

The dominance of memes and viral posts from the USA celebrating a brat summer was challenged in late August by a TikTok injunction to ‘be demure and mindful‘ in all one’s actions and representations. Alternative and mainstream media jumped quickly aboard the accelerating bandwagon – and Ellie Bramley of the Guardian asked me to comment…

‘Demure‘ is a seemingly prim and dated adjective, used recently only by rueful babyboomers and tabloid journalists, for whom it is code for ‘not completely undressed’ when describing female celebrities attending film festivals, tottering along red carpets and catwalks. In drag queen and ‘ballroom LGBT‘ circles, though, it has long featured as a self-mocking keyword when urging the outrageous, usually ironically and teasingly, to behave with modesty and decorum. It is in this spirit that ‘fierce divas’ and other influencers have relaunched the term, along with ‘mindful‘ in its older sense (before the advent of self-seeking ‘mindfulness’) of considerate, respectful and cautious. The Guardian piece is here…

It’s very easy to dismiss GenZ and TikTok fads as shallow, ephemeral provocations, unworthy of the attention of rational adults. Easy, too, to deride aged babyboomers like me who record them and attempt to analyse the thinking behind them. But as Ellie herself remarked, a keyword like ‘demure’, inasfar as it isn’t just an absurdist gesture, can not only signify a genuine shift in self-awareness on the part of a few influential online individuals, but can prompt reflection and even changes in behaviour among a much larger segment of the population.

With that in mind, from Laura Pitcher, here’s Dazed‘s perceptive take on the word of the moment…

In September I was interviewed by Mary Ugbodaga about a slang acronym in use in Nigeria…

WSG meaning: what does the acronym mean and how to respond – Legit.ng