Some new thoughts about the pervasive, destabilising, discomfiting Language of Lying in public life

In 2015 Conservative politician Grant Shapps was forced to admit that he had ‘over-firmly denied’ having a second job under a pseudonym, selling a ‘get-rich-quick’ scheme while sitting as an MP.

In 2008 Hillary Clinton admitted that she had ‘misspoken’ when she claimed to have come under sniper fire during a 1996 visit to Bosnia.

A slang phrase, borrowed from US street and hiphop parlance into so-called MLE, ‘multicultural London English’, and often used by teenagers in London today, is ‘no cap!’ an exclamation which is the modern equivalent of the adult ‘no word of a lie!’ when swearing that you can be trusted, are being sincere, are telling the truth.

Orwell famously exposed the doublespeak of totalitarianism and I wrote some years ago about politicians’ evasive and duplicitous ‘weasel-words’ (a version of the article is on this site). In the late 90s I presented a series for the BBC World Service in which we looked at the politics of ‘spin’ and the work of the spin-doctors employed first by Bill Clinton and later by Tony Blair to massage their messages and to take ownership of the media narratives of the moment. The half-truths and untruths perpetrated today are more frequent, more widespread, some are more flagrant, and all are helped in their trajectories by multiple new platforms and outlets and far more sophisticated mainstream and social media capabilities.

I have collected examples of the toxic terminology and ‘skunked’ terms employed by demagogues and charlatans and echoed by compliant journalists and commentators (my glossary is on this site). In the media maelstrom we are presently living through, untruths, half-truths and fake news, too, have featured prominently and repeatedly in the national conversations of the US and the UK. With this in mind the Open University has produced a two-part mini-documentary on the Language of Lying in which I was privileged to take part. We talk about the concepts of truth and falsehood and about their incarnations in the current context of populism, Trumpism and Brexit.

Part One of the documentary is here:

I’m very grateful to Dr Philip Seargeant of the OU for initiating this project and asking me to take part, grateful too to Hamlett Films for producing the programme.

Here is the second part:

And here are links to two more recent commentaries on lying:

Acting Dishonestly Impairs Our Ability To Read Other People’s Emotions

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/10/trump-lies-kavanaugh-khashoggi.html

and in December Richard Sambrook reflected on the way that traditional norms of political and media behaviour had been abandoned in the 2019 election campaign:

In November 2019 we had news of the world’s biggest liar:

A happy footnote: the OU documentary in which I took part won the Medea Award, announced in October 2020:

Click to access MEDEA-Awards-2020_press-release_Winners_20201028.pdf

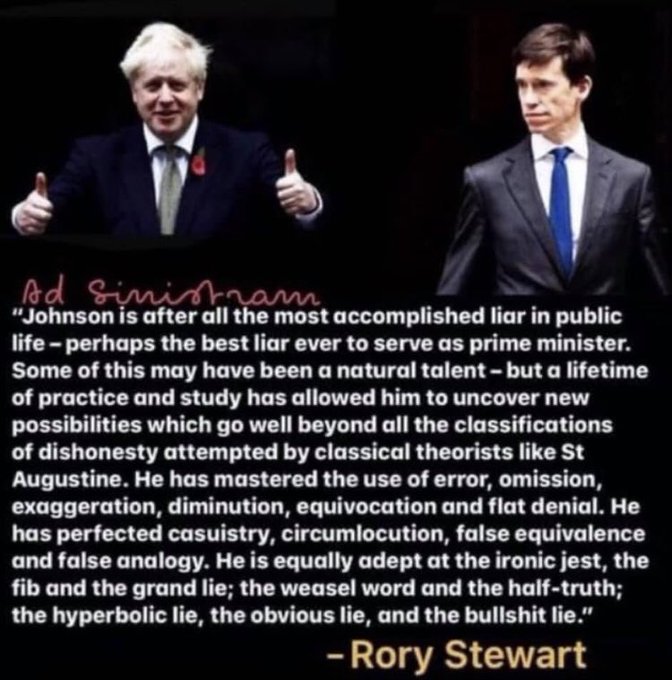

By way of an update, in May 2021 Conservative MP Rory Stewart delivered this assessment of Prime Minister Boris Johnson:

Then, in June…

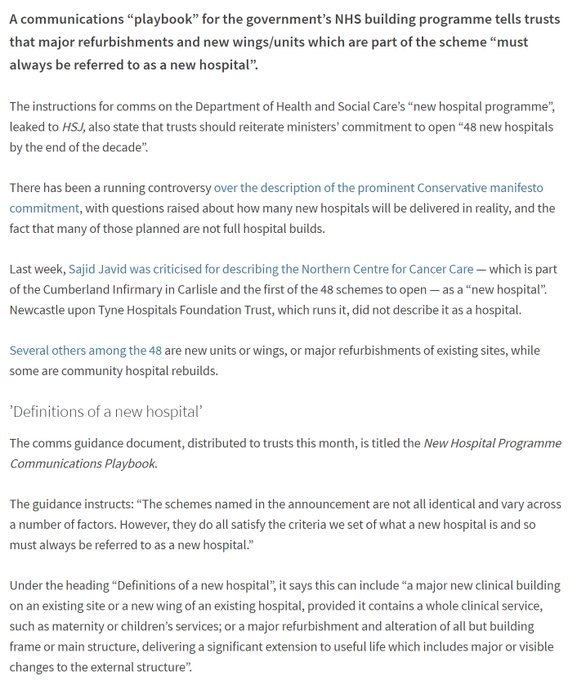

In August 2021 the UK government deployed a comms strategy that commentators referred to variously as ‘spin’, ‘stretching the truth’, ‘newspeak’… and ‘institutional lying’…

In January 2022, as Boris Johnson faced a tide of indignation following revelations of lockdown breaches (the so-called ‘partygate’ scandal), Journalist Peter Oborne published a list of what he charitably termed ‘misleading statements’ made by the Prime Minister and still uncorrected in official records…

https://boris-johnson-lies.com/johnson-in-parliament

In April 2022 The Conversation challenged the view that the UK public were inured to lying by politicians…

But by 2026 little had changed. Wales, at least, was debating the issue…reported again by The Conversation…

One country is trying to outlaw political lying, without curbing free speech

/Shah_Jahan_1628wiki-56a0424b5f9b58eba4af918d.jpg)